Cécile Lecoq | LinkedIn | Twitter

Selected final essay, published 5 Oct 2020

Cécile is passionate about cities and mobility. She lives in Gatineau, Canada, with her husband and two sons, and together they have happily embraced car-free living. As a transit professional and cycling advocate, Cécile is relentlessly working to make her city more equitable and sustainable.

Unraveling the Cycling City MOOC on Coursera

When we think about encouraging more people to bike, we tend to focus solely on infrastructure. This mindset is embodied in the phrase “build it and they will come” that is often heard among bike advocates. While ensuring people’s safety is a sine qua non condition, it is not the only aspect of a successful cycling culture, as demonstrated by the “Unraveling the Cycling City” online course.

The Dutch cycling culture is the result of a “combination of factors, including bicycle-friendly representations, strong bourgeois cultures, urban-planning choices, late automobility, and governmental policies” (Oldenziel and de la Bruhèze 2011). Indeed, the key to getting people on bikes is “the coordinated implementation of a multi-faceted, mutually reinforcing set of policies” (Pucher and Buehler 2008).

Among the historical factors that contributed to the success of cycling in the Netherlands were public outcry in reaction to traffic deaths, such as the famous Stop de Kindermoord protests, which, combined with the 1973 oil crisis and its financial impacts, got the national and municipal governments to implement policies in favour of cycling (Zee 2015). In addition, the ban on big box stores on the outskirts of towns enabled city centres to prosper and every neighbourhood to get its own small-scale retail stores.

Some idiosyncratic characteristics of the Netherlands also contributed to a wide adoption of the bicycle: its flat topography and mild climate, as well as its homogenic and strongly integrated egalitarian culture (Kuipers 2013).

All these conditions formed a system of self-reinforcing feedback loops where a high cycling modal share led to the organization and development of cities, neighbourhoods and transit systems around the bicycle, and vice versa. Nowadays, cycling is so integrated in the Dutch lifestyle that it is felt as self-evident.

Understanding how the Dutch cycling culture came about allows us to grasp the difficulty of replicating this success elsewhere, especially in countries that have continued to invest heavily in autocentric infrastructure for the past 50 years. Cities such as my home town of Gatineau, Quebec, will have to find their own paths towards making cycling mainstream.

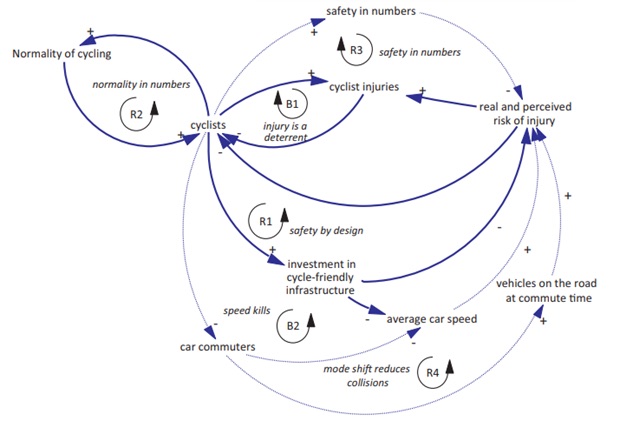

Macmillan and Woodcock (2017) used system dynamics modelling to establish which policies are needed, and in what order, to achieve an increase in urban cycling. The 3 cities they studied (Auckland, London and Nijmegen) had common reinforcing patterns: “growing numbers of people cycling lifts political will to improve the environment; cycling safety in numbers drives further growth; and more cycling can lead to normalisation across the population” (cf. Figure 1). They conclude that cities with very low levels of cycling need to improve its actual and perceived safety and strengthen the positive feedback loop between the number of people cycling and investment in infrastructure.

However, they leave out the longer term but crucial mutual relationship between transportation and land use. In cities built around the automobile, even with adequate cycling infrastructure, the segregation of uses and hostile environments created by wide arterial roads and large malls surrounded by parking make the bicycle a less efficient and attractive transportation option.

Creating mixed-use, 15-minute neighbourhoods may be the best way to reduce car dependence and favour active transportation. The location of daycare centres and schools is especially important to facilitate trip chaining, which women still tend to do more of, and achieve a better gender balance in cycling rates. As stated by Bertolini and le Clercq (2013), “the continued success of walking and cycling environments also depends on the extent to which new and existing residential areas are able to develop a critical mass of destinations (such as workplaces and facilities) within short distances.”

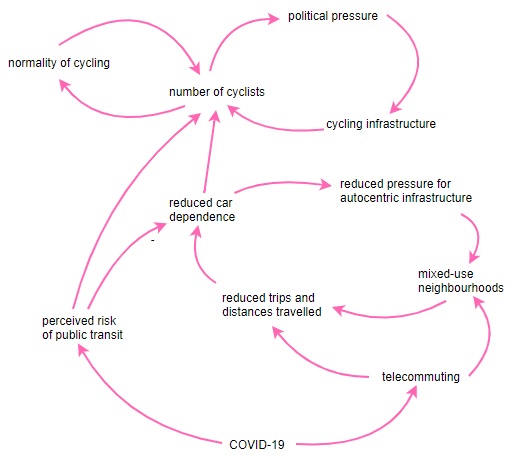

In this respect, it will be interesting to see if the increase in telecommuting due to the COVID-19 crisis will last, and what impacts it could have on cities and mobility. By reducing the frequency and length of commuting trips, this trend could lead to a reduction in car ownership in favour of more active transportation and carsharing. It could provide incentives for more diverse service offerings in residential areas and for mall redevelopment projects. It could also reduce political pressure for autocentric infrastructure and free budgets for active transportation. Figure 2 shows a simple example of the feedback loops that could generate an increase in urban cycling, although more balancing forces would probably seek to maintain the status quo.

In dense cities where land use is already adequate, the shift towards urban cycling can happen very quickly. An interesting example is Paris, where the combination of a month-long transit strike, the COVID-19 crisis and the quick installation of pop-up bike lanes has given rise to a wide adoption of biking as transportation. Parisians of all ages now cycle in casual clothes on all kinds of bicycles, including Vélib’ and other shared bikes.

This success gives many cycling advocates hope for their own cities. But we have to reiterate that for cycling to thrive, we need a multifaceted set of policies. As the Dutch example shows, building a successful cycling culture requires a systemic approach.

Photo by @AilesCyclables

—-

References:

- Bertolini, L. & le Clercq, F. (2003). Urban development without more mobility by car? Lessons from Amsterdam, a multimodal urban region. Environment and Planning A, 35(4), 575–589.

- Kuipers, G. (2013). The rise and decline of national habitus: Dutch cycling culture and the shaping of national similarity. European Journal of Social Theory, 16(1), 17–35.

- Macmillan, A., Connor, J., Witten, K., Kearns, R., Rees, D. & Woodward, A. (2014). The Societal Costs and Benefits of Commuter Bicycling: Simulating the Effects of Specific Policies Using System Dynamics Modeling. Environmental Health Perspectives, 122 (4).

- Macmillan, A. & Woodcock, J. (2017). Understanding bicycling in cities using system dynamics modelling. Journal of Transport & Health, 7, 269-279.

- Oldenziel, R. & de la Bruhèze, A. A. (2011). Contested Spaces: Bicycle Lanes in Urban Europe, 1900–1995. Transfers, 1(2), 29–49.

- Pucher, J. & Buehler, R. (2008). Making Cycling Irresistible: Lessons from The Netherlands, Denmark and Germany. Transport Reviews. 28(4), 495–528.

- Zee, R. van der (2015). How Amsterdam Became the Bicycle Capital of the World. The Guardian, May 5, 2015.