“Becoming an urban cyclist” is not only about acquiring a set of skills to get on a bike, pedal and weave in and out between the cars but it also changes people’s perception of space, time and the city, as well as of other road users; it changes their way of moving and interacting with others. It leads to the discovery of new places, new physical and mental sensations and emotions.

(Adam & Ortar, 2022: xx-xxi)

What is it about?

How can we understand the process of “becoming” a cyclist concerning perceptions, lived experiences, practices, and identities? Is there any significance to the skills and knowledge related to the different forms of socialization? And what can we learn from geographical and sociological differences to facilitate urban cycling?

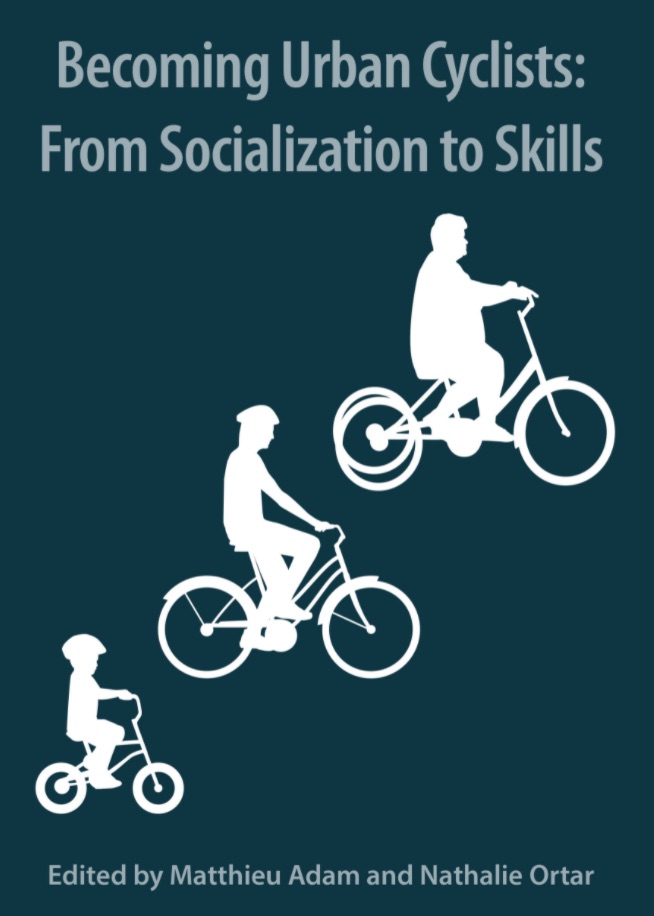

Becoming Urban Cyclists tries to explain how we can become urban cyclists “again” after a decline in the mid-20th century. By considering a variety of skills and a set of knowledge that can be achieved through different forms of socialization, we can promote the growth of urban cyclists. In my opinion, this approach can be placed within the larger framework that has already been proposed as hard and human infrastructure (Lugo, 2013; Snaije, 2021). The authors aim to describe who can be an urban cyclist and how, and how this in turn contributes to shaping specific identities, perceptions, and practices.

There is no doubt that we need to come back to the bicycle as a new old thing (Lugo, 2013; Vivanco, 2013) in order to address dramatic environmental challenges by becoming cyclists in various socio-spatial configurations. Becoming a cyclist is the story of transforming our lived experience in relation to space and people.

“Becoming expresses our interest for the process by which people acquire the skills and knowledge necessary for cycling in the city, a process that might vary with culture, gender and social space, but also with topography, residential as well as occupational location, the social environment in which the cyclist grew up, and more”

(Adam & Ortar, 2022: xx)

This book follows a workshop organized in Lyon (France) in February 2020 that brought together researchers from different backgrounds (sociology, anthropology, and geography), studying different cities and countries (Australia, France, Germany, Switzerland, United Kingdom) and using various quantitative and qualitative methods.

What approach does it take?

Becoming an urban cyclist can vary with culture, gender, and social space. This book, therefore, focuses on this process through “biographical approaches” to understand the Practices of becoming a cyclist and the development of city cycling. “Materials”, “competences”, and “meanings” are interconnected elements of cycling practices that influence each other; competences and meanings are linked to socialization which has intimate connections with the bike, environments, and biological bodies as the materials. This book is divided into nine chapters discussing both socialization to bicycle mobility (learning of the practice as such: how to ride, fit in with the traffic, park, etc.) and socialization through bicycle mobility (how cycling leads to learning about a city or about other road users, how it changes people’s identity, etc.).

The authors describe the process of “becoming urban cyclists” as a socialization process and the relationship between urban cycling and inequalities in the introduction. In Chapter 1, Becoming an Urban Cycling Space, Peter Cox takes an historical, political, and comparative perspective to examine the ups and downs of urban cycling from the 19th century to today, tracing the changes in mobility during the pandemic. Has Covid-19 Remade the Cycling City? In Chapter 2, Conducting Interviews with Maps and Videos to Capture Cyclists’ Skills and Expertise, Matthieu Adam, Nathalie Ortar, Luc Merchez, Georges-Henry Laffont and Hervé Rivano focus on mixed methods (GPS tracking, video recording, and interviews) to capture cyclists’ lived perceptions related to cyclability which refers to the capacity of spaces to accommodate, facilitate and ensure the safety of cycling practices. In chapter 3, Key Events, Motivations and Prior Experience in E-Bike Adoption, Dimitri Marincek tries to explore factors that prompt city dwellers in Switzerland to adopt e-biking by taking a biographical approach and focusing on turning points in the life course.

Patrick Rérat discusses awareness campaigns in Chapter 4, The Effects of a Promotional Campaign on the Practice of Utility Cycling: Bike-to-Work in Switzerland, as a tool for promoting urban cycling in various contexts. In his article, he describes how planning interventions can make cycling more attractive, efficient, and safe for a diverse range of people. M. Cristina Caimotto uses an ecolinguistic approach to analyze cycling-related documentations in chapter 5, Promoting Urban Cycling: An Ecolinguistic and Discursive Approach, to explain how cycling promotion disseminates values, and its social and political implications. The author focuses on cycling discourses used by different actors in order to discover what a defendable cycling discourse is. In Chapter 6, Adult Beginner Cyclists in French Cities, Thomas Buhler conducts a quantitative transport panel survey to estimate adult beginner cyclists, who cycle for utility purposes on a rather regular basis but with low cycling skills, and their characteristics.

The purpose of Chapter 7, Immigration Background and Cycling Findings from Germany, is to examine the behavioral differences between cyclists from immigrants and non-immigrant backgrounds in Germany based on a quantitative telephone survey and a qualitative interview. In Chapter 8, What Makes Women Stop or Start Cycling in France? David Sayagh, Clément Dusong and Francis Paspon, use the quantitative interview method to answer this question. In chapter 9, Appropriating the Bicycle: Repair and Maintenance Skills and the Bicycle-Cyclist Relationship, Margot Abord de Chatillon compares attitudes between cyclists who are inexperienced in repairing and maintaining their bikes and those for whom repair and maintenance are easy and frequent activities. Through interviewing cyclists in Melbourne and Lyon, this paper sheds light on how repair skills are acquired.

Who might be interested in this book?

The book will appeal to anyone seeking to understand the process of becoming a cyclist in different socio-spatial contexts and learn from the variety of mixed methods research looking at urban cycling. It is a great opportunity for readers to get familiar with cycling culture in different cities and countries. All we need to promote urban cycling is make sure that we are moving in the right direction; this book is an excellent resource to help us do so.

Further details

- Academic disciplines: Mobilities, planning, urban sociology, and anthropology.

- Geographical scope: Australia, France, Germany, Switzerland, and United Kingdom.

- Relation to cycling: Cycling is central in this book; Through a multidisciplinary approach utilizing different perspectives, the book sheds light on geographical and sociological differences to help understand factors likely to facilitate or curb urban cycling practices.

- Reference (APA): A. Matthieu & N. Ortar (Eds.). (2022). Becoming urban cyclists: From socialization to skills. University of Chester Press.

- Reference in text:

- Lugo, Adonia E. 2013. “CicLAvia and human infrastructure in Los Angeles: ethnographic experiments in equitable bike planning.” Journal of Transport Geography 202-207.

- Snaije, L. (2021). Strengthening the Human Infrastructure of Cycling: soft strategies for inclusive uptake. BYCS.

- Vivanco, L. A. (2013). Reconsidering the bicycle: An anthropological perspective on a new (old) thing. New York: Routledge.